Haiku

Originating in Japan, haiku traditionally have a seasonal reference and give insights into Mother Nature as well as human nature (a senryu). Although the common syllable count is 5/7/5, this has been relaxed in contemporary haiku to prevent “padding” or softening of the language.

Haiku are composed of three lines with a break or gap usually between the second and third line. The first two lines are referred to as “the base” and the third line creates what is known in the haiku world as the “aha moment”. The single line animates the image in the first two lines and there’s a leap in consciousness.

Haiku are based on what is unique to our own experience. We all have reactions, sensations, preferences, emotions, insights and thoughts that develop in our minds over time. Haiku draw off this repository, ignited by a certain image. This is often fueled by our moods as well. Haiku is all about self-expression but it delivers a universal message.

The seasons are the essence of haiku. They root the image in nature and time. They are usually implied in the base to orient the reader. Seasonal words are the most common way to do this. Each season has its own language and sensations. These are in ever-changing relation to one another.

Haiku are a whole world in three lines.

branch low

over the worn trail

how many know you?

The image and setting comprise the “base” which is the first two lines:

branch low

over the worn trail

The third line breaks the blandness of the first two lines and creates the universal “aha” moment:

how many know you?

Haiku are a whole world in three lines.

branch low

over the worn trail

how many know you?

The image and setting comprise the “base” which is the first two lines:

branch low

over the worn trail

The third line breaks the blandness of the first two lines and creates the universal “aha” moment:

how many know you?

Here the haiku is a whole world in a three line poem:

branch low

over the worn trail

how many know you?

The image and setting comprise the “base” which is the first two lines:

branch low

over the worn trail

The third line breaks the blandness of the first two lines and creates the universal “aha” moment:

how many know you?

The practice of haiku is to have it meet your senses directly, to connect with what you were seeing and thinking at the time you wrote the haiku. This happens subconsciously and the haiku makes it conscious. Then someone else can read it and also be present in that moment.

Madeleine Findlay

Madeleine Findlay was born and raised in New Jersey. In 1971, she graduated from The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with a BFA in Graphic Design. Photography was her main interest until she discovered haiku in 2001. In 2006, she founded Single Island Press to promote and publish contemporary haiku inspired by the masters beginning with Basho in the 17th century.

Her interest in haiku had its origins in her Degree Project at RISD, resulting in a one-of-a-kind book combining seasonal images of an Adirondack Mountains retreat with excerpts from T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets”. The theme was the paradox of change and timelessness. After many years of working with this topic using various media, she discovered haiku contains three main ingredients with which she was familiar: poetry, place and image. Her evolving passion for haiku has inspired her to create and share “haiku spirit”.

Books Published: Shaped Water (First Edition 2007, Second edition 2008); Empty Boathouse: Adirondack Haiku (2008) which won second Place, Haiku Society of America 2008 Mildred Kanterman Memorial Merit Book Award, for excellence in published haiku; Under the Moon: Haiku and Senryu (2012).

Linda Coe

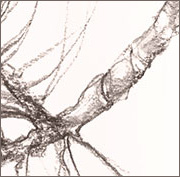

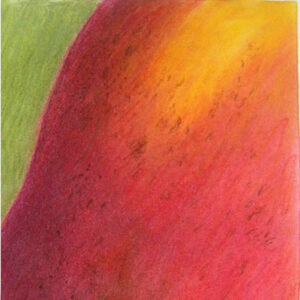

Linda Coe has a passion for drawing. Raised in Washington, D.C., she studied art at Wellesley College, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Corcoran School of Art. She has also taken courses in scientific illustration at the Smithsonian and Harvard University’s Peabody Museum.

Her favorite medium is the ordinary graphite pencil. Occasionally she will include watercolor or conte crayon washes. The life and spontonaiety of line have always been important to her – the immediacy of line, its infinite and subtle capacity for conveying strength, delicacy, rhythm, sensuality and texture.

She prefers to draw objects from nature: fruit, flowers, trees, pods. Each is its own world to her, so she does not place them in another space or time. She prefers to capture a moment, memorializing their simultaneous life force and decay, seeing the objects as a metaphor for cycles of life and death.